If its members wish to reclaim the place for the Conference on Disarmament that was envisaged by its founders, they must return to seeking multilateral agreements.

The deteriorating international security environment continued hindering the multilateral disarmament machinery throughout 2019. The unresolved matter of the issuance of visas affected disarmament organs at the United Nations Headquarters, resulting in the cancellation of the annual session of the United Nations Disarmament Commission and a delay of the substantive session of the First Committee of the General Assembly. The States members of the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva failed to overcome the deadlock that has lasted over two decades.

The work of the First Committee was overshadowed by growing tensions among major powers, particularly between the United States of America on one side and China and the Russian Federation on the other. Yet, despite the challenging global security environment and the considerable time devoted to addressing matters not necessarily related to its substantive work, the First Committee fulfilled its mandates for the year, approving 59 draft resolutions and decisions under various agenda items.

Separately, the States members of the Conference on Disarmament continued their efforts to begin substantive work, building on momentum created during the 2018 session. However, although proposals for a programme of work for 2019 were introduced by three presidencies of the Conference—Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Ukraine and Viet Nam—the Conference did not reach agreement on a proposal and, again, failed to start substantive work. With little prospect of adopting a programme of work, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which assumed the second presidency in mid-February, sought to establish new subsidiary bodies and special coordinators with a view to structuring the current session to build on progress from the previous year. Yet, despite the efforts of the United Kingdom presidency, agreement on its proposal proved elusive.

Nevertheless, consultations held under each of the six presidencies in 2019 enabled the Conference to discuss and examine various possibilities and potential language for a programme of work. In particular, during the presidency of Viet Nam, the Conference considered alternative approaches inspired by a suggestion put forward by the Netherlands to return to an earlier conceptualization of the programme of work. In a broader effort to commence substantive work, the Conference also held extensive thematic discussions on all core agenda items, while continuing to consider its working methods and the possible expansion of its membership. Despite more than two decades of paralysis in the Conference, a growing level of interest in its work was apparent from the requests of 50 States—a record number—to attend the 2019 session as observers.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres addresses the Conference on Disarmament's High-Level Segment 2019, Palais des Nations, 25 February 2019. UN Photo by Antoine Tardy.

Tatiana Valovaya (left), Director-General of the United Nations Office at Geneva and Secretary-General of the Conference on Disarmament, speaks with Izumi Nakamitsu, High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, during the third part of the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, 26 August 2019. UN Photo/Jean Marc Ferré

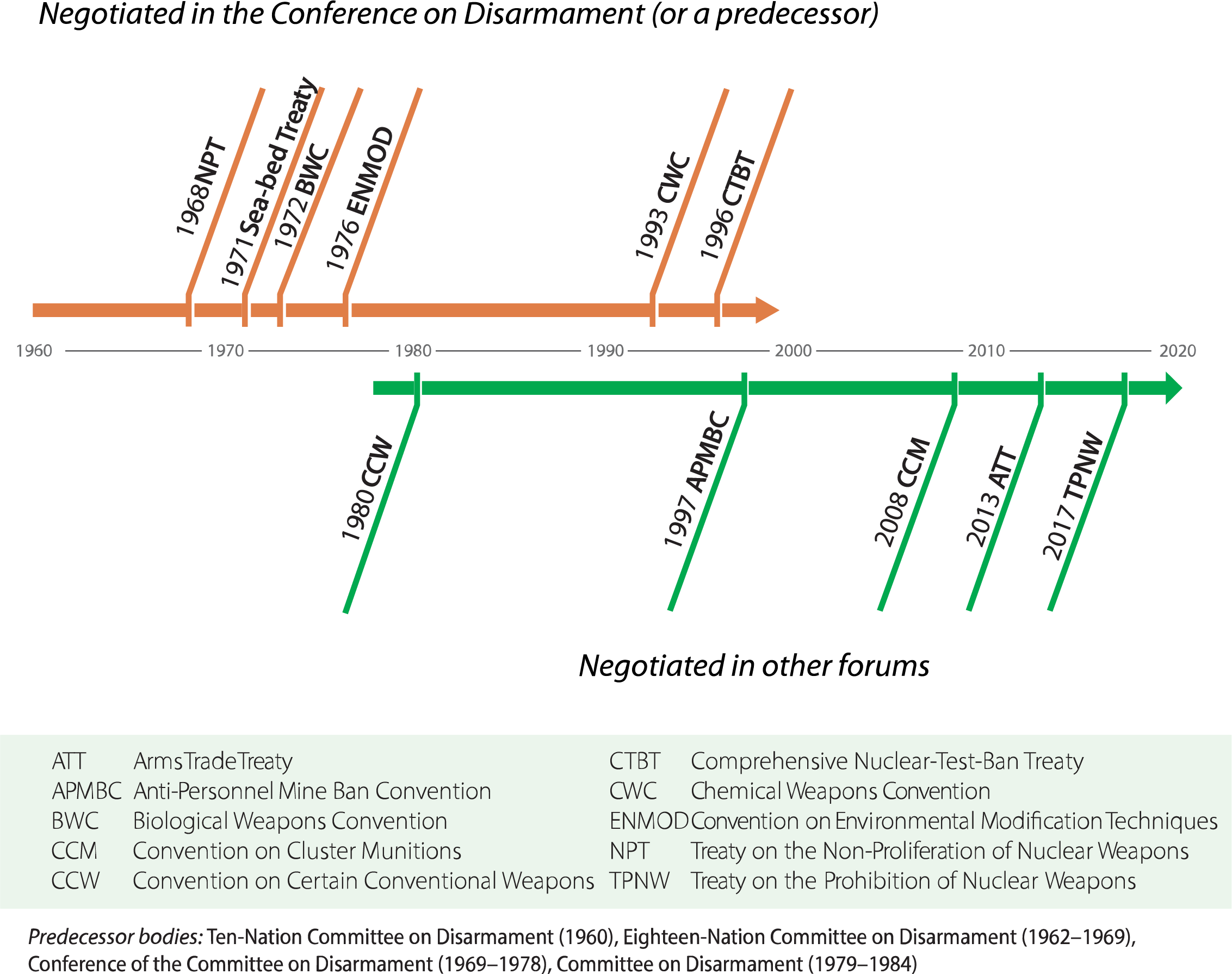

The international community has maintained a single negotiating body since the 1960s for Governments to develop and agree on new multilateral disarmament treaties that are open to all States. Today’s forum is called the Conference on Disarmament and offers a venue for its member States to regularly meet to pursue new disarmament measures by consensus.

The Conference on Disarmament in Geneva built on the legacy of its predecessor institutions well into the 1990s, most notably through the development of the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. Since 1996, the body has not negotiated new legal instruments.

Countries have initiated ad-hoc processes to negotiate a treaty regulating the conventional arms trade as well as separate bans on landmines, cluster munitions and nuclear weapons.

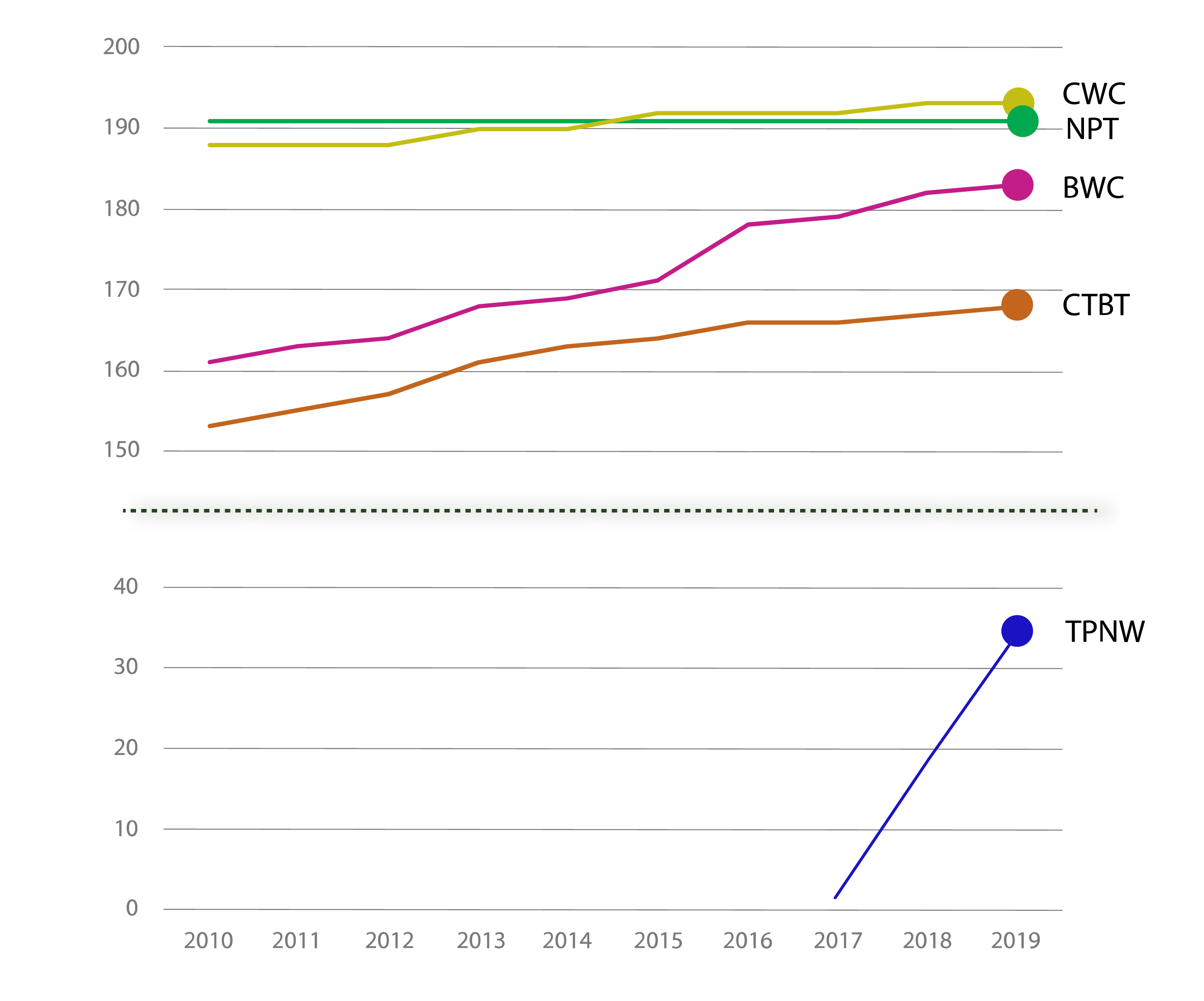

Over the past decade, membership in multilateral treaties related to disarmament and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction has continued to increase. In that time, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have achieved near-universal status, with the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) both making significant strides towards that end. After its adoption in 2017, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) continues to make steady progress towards the threshold of 50 ratifications required for its entry-into-force. Taken together, these trends indicate that, even in the face of a difficult and deteriorating global security environment, States continue to value multilateral treaties related to the elimination of all weapons of mass destruction and the security benefits that they provide.

Elsewhere, the United Nations Disarmament Commission was unable to hold its substantive session for the first time since 2005, dealing a blow to the effort to revitalize the multilateral disarmament machinery. Following its successful adoption in 2017 of recommendations on confidence-building measures in the field of conventional weapons, the Commission had started a new three-year cycle in 2018, addressing one fresh substantive agenda item, entitled “Transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space activities”, alongside an existing item on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. The Commission was unable in 2019 to complete its organizational session and, therefore, could not hold its substantive session from 9 to 25 April, as mandated by the General Assembly in its resolution 73/82 of 5 December 2018. Nevertheless, Member States held informal discussions on the two agenda items of its current three-year cycle in a bid to advance the deliberations on those issues.

Additionally, the Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters held its seventy-first and seventy-second sessions, addressing two substantive agenda items. Regarding the first item, “Measures to mitigate civilian harm resulting from contemporary armed conflict”, the Board, inter alia, recommended encouraging the General Assembly to further consider the issue of the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, potentially leading to mandates for the further development of criteria, indicators and methodologies to measure the reverberating civilian impacts of such use. In addition, the Board recommended developing a systematic approach and consistent methodologies to pool data on the effects of such use of explosive weapons, possibly including economic effects in order to underscore the multidimensional impact. On its second substantive agenda item, “The role of the disarmament, arms control and non-proliferation regime in managing strategic competition and building trust”, the Board encouraged the Secretary-General to continue his high-level engagement with the five permanent members of the Security Council on the importance of cooperation aimed at reducing strategic competition and nuclear risks. The Advisory Board also highlighted the potential value of further engagement by the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs to identify options aimed at reversing current impediments to progress on disarmament. In that connection, its members called for a forthcoming study by the Office for Disarmament Affairs to include a review of the state of existing disarmament machinery.