Building a better understanding of the impact of emerging technologies on international peace and security has become a key requisite for ensuring this Organization is fit to meet the challenges of the future.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic’s continued impact on multilateral disarmament and arms control processes throughout 2021, the international community achieved important progress during the year on several emerging challenges related to developments in science and technology and their implications for international peace and security.

Regarding outer space, the General Assembly decided in December to establish a new open-ended working group in 2022 to develop recommendations on, inter alia, norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviours (76/77). That mandate followed the issuance in July of a substantive report of the Secretary-General, developed pursuant to resolution 75/36. The United Nations Disarmament Commission, which had adopted an agenda item on outer space for consideration during its 2018–2020 cycle, was again unable to convene its substantive session owing to unresolved procedural issues relating to the issuance of visas for certain delegations. (For more information on the Disarmament Commission, see chap. VII.)

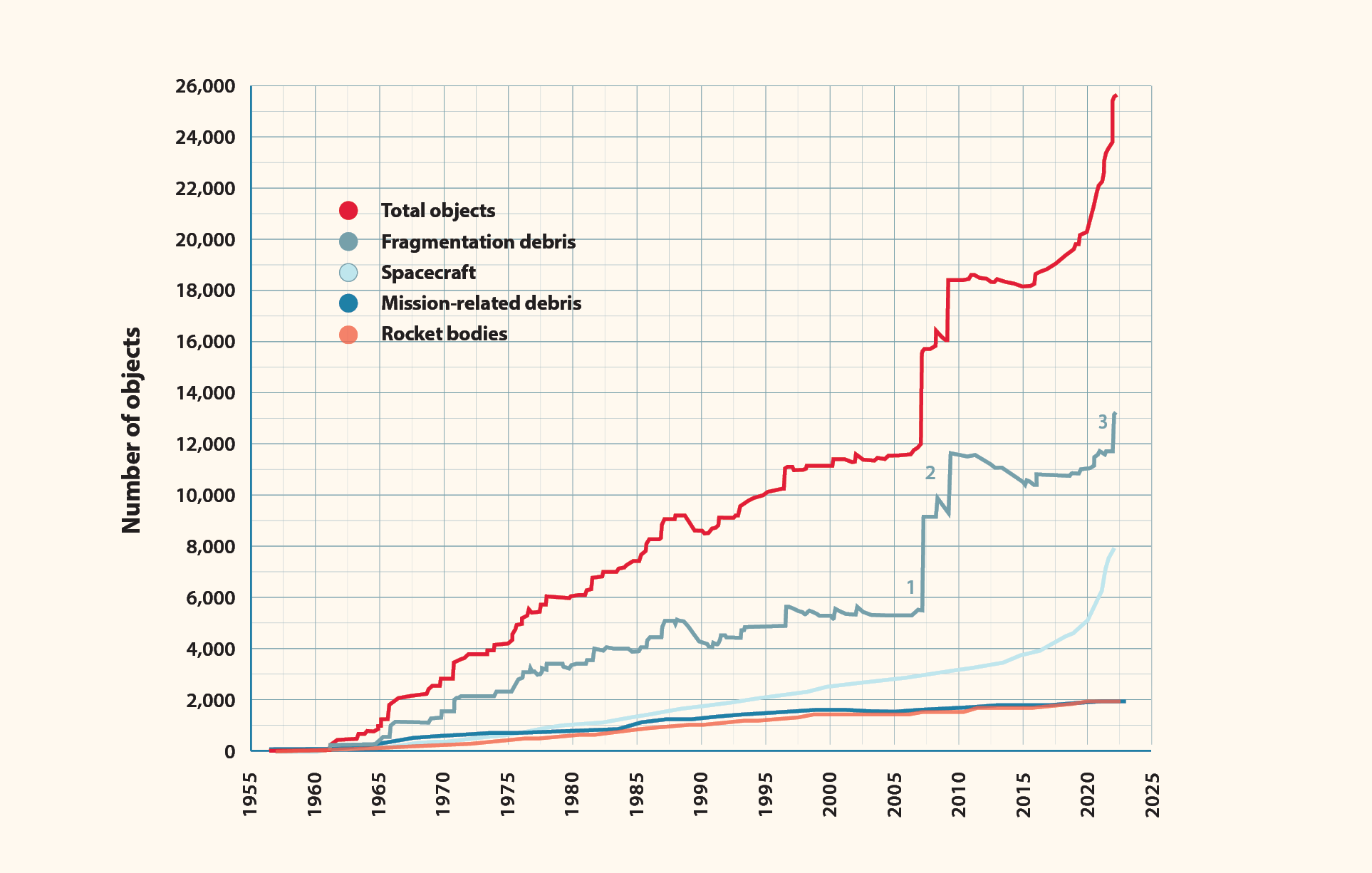

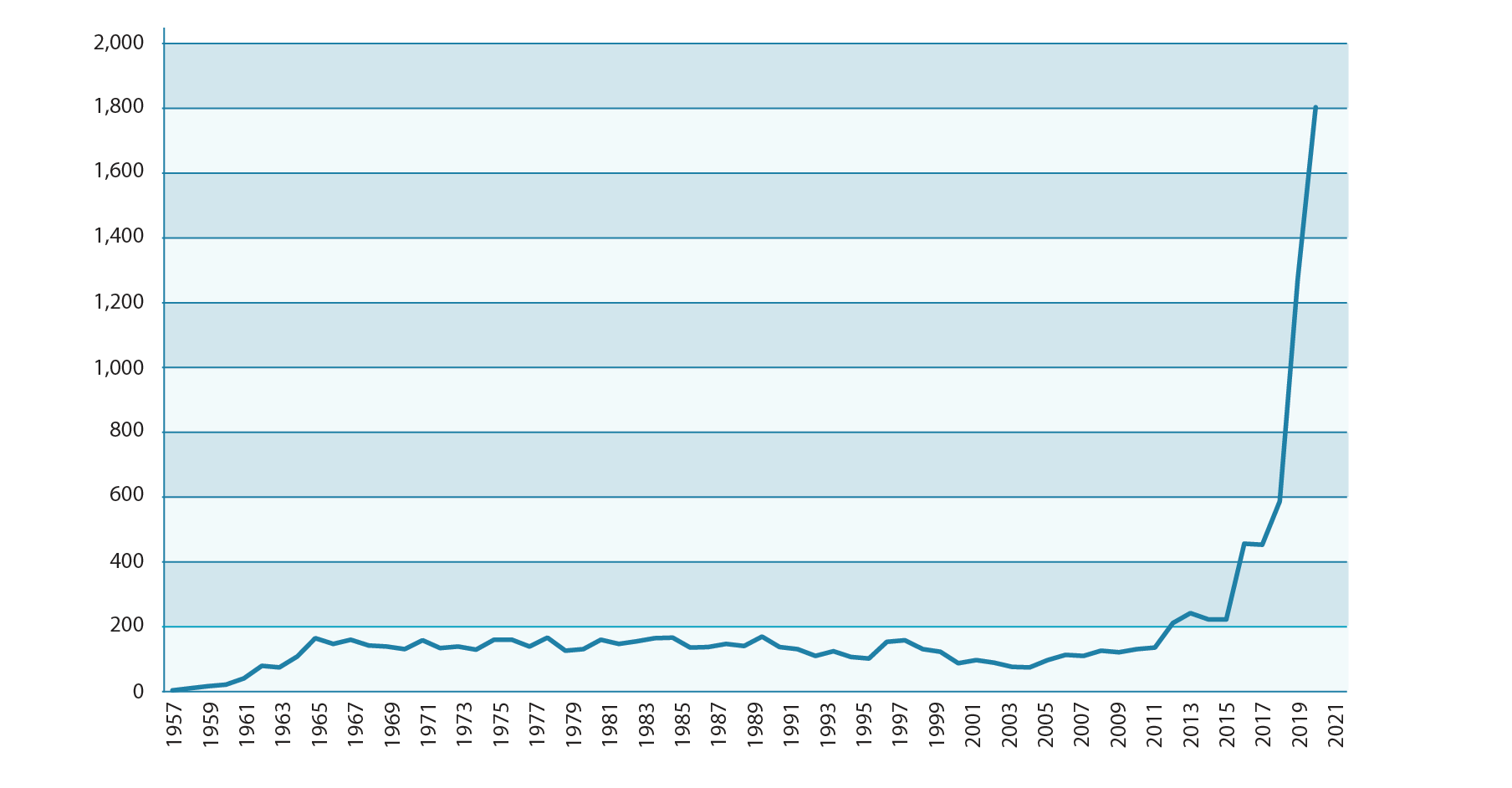

Since the launch of the first satellite in 1957, the number of objects in low Earth orbit has grown to nearly 26,000 by the end of 2021. Destructive tests of anti-satellite weapons and collisions between space objects can cause significant increases in the amount of fragmentation debris. The deployment of mega-constellations is contributing to the accelerating increase in the total number of functional satellites.

Total number of orbiting items by year as reflected in the “Online Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space”, maintained by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs.

On information and communications in the context of international security, the two previously established intergovernmental processes in that field successfully concluded their respective work with the adoption of consensus reports (A/76/135 and A/75/816). A new open-ended working group commenced its work in 2021 under a five-year mandate, holding its organizational session in June and its first substantive session in December. In the General Assembly, the Russian Federation and the United States tabled a joint resolution on the relevant agenda item (76/19), returning to a single consensus text on the subject.

Using information and communications technologies to intentionally damage or impair the use and operation of critical infrastructure providing services to the public can have cascading domestic, regional and global effects. Such activities pose an elevated risk of harm to the population and can be escalatory.

The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened awareness of the critical importance of protecting health-care and medical infrastructure and facilities from malicious activity using information and communications technologies.

Against this backdrop, States have endorsed concrete norms of responsible State behaviour that support the protection of critical infrastructure, including the following:

A State should not conduct or knowingly support ICT activity contrary to its obligations under international law that intentionally damages critical infrastructure or otherwise impairs the use and operation of critical infrastructure to provide services to the public.

Examples of critical infrastructure sectors that provide essential services to the public are shown in this graphic (see also A/76/135, para. 45).

On autonomous weapons systems, the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems agreed only on annexing to its report the draft conclusions and recommendations submitted by the Chair and discussed by the Group, on which no consensus was reached. The sixth Review Conference of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons included language in its declaration and adopted a new mandate for the group to resume work in 2022. (For more information, see chap. III.)

United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs personnel conversing with representatives of non-governmental organizations and think tanks on the margins of the twentieth United Nations-Republic of Korea Joint Conference on Disarmament and Non-proliferation Issues, held in Seoul in November 2021.

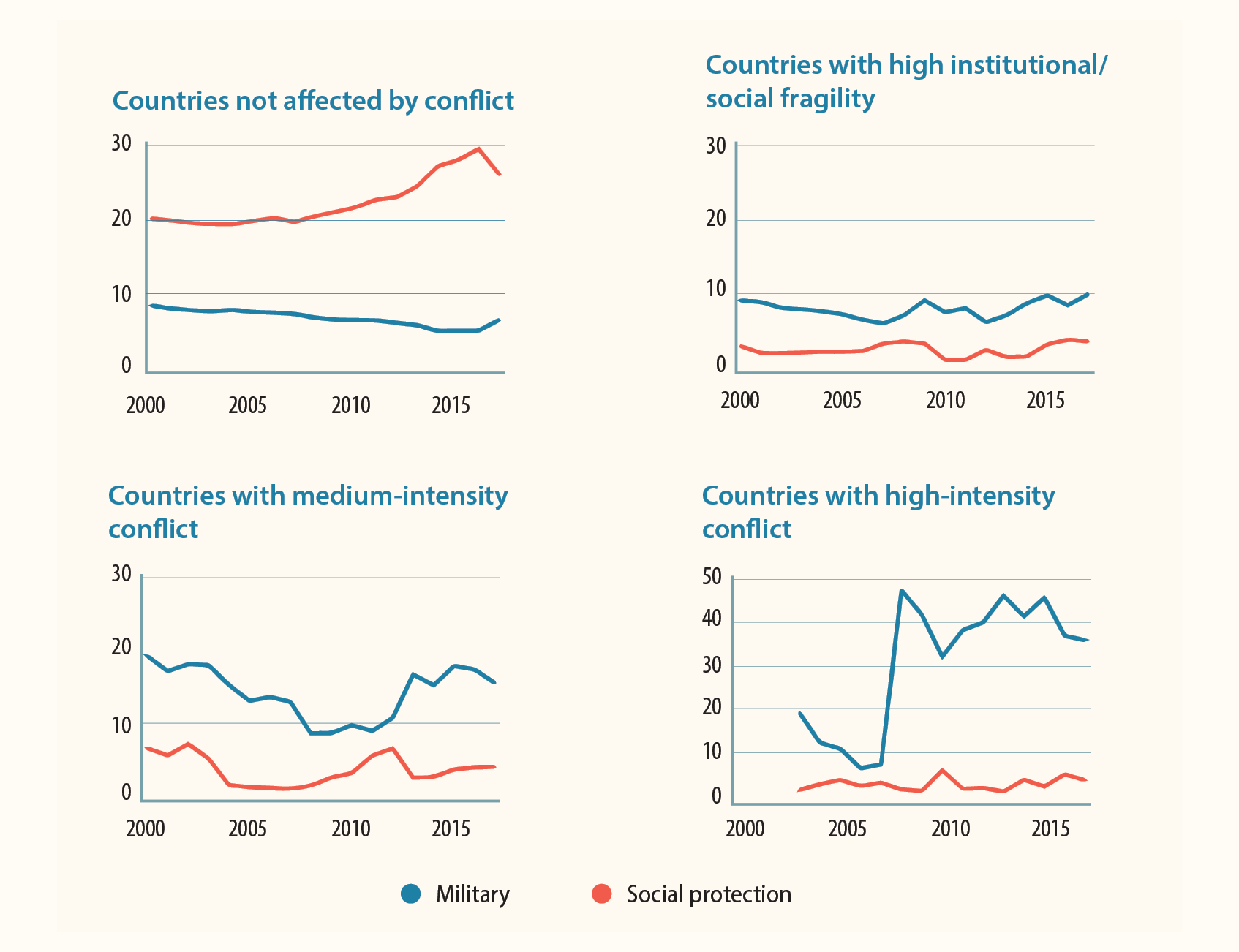

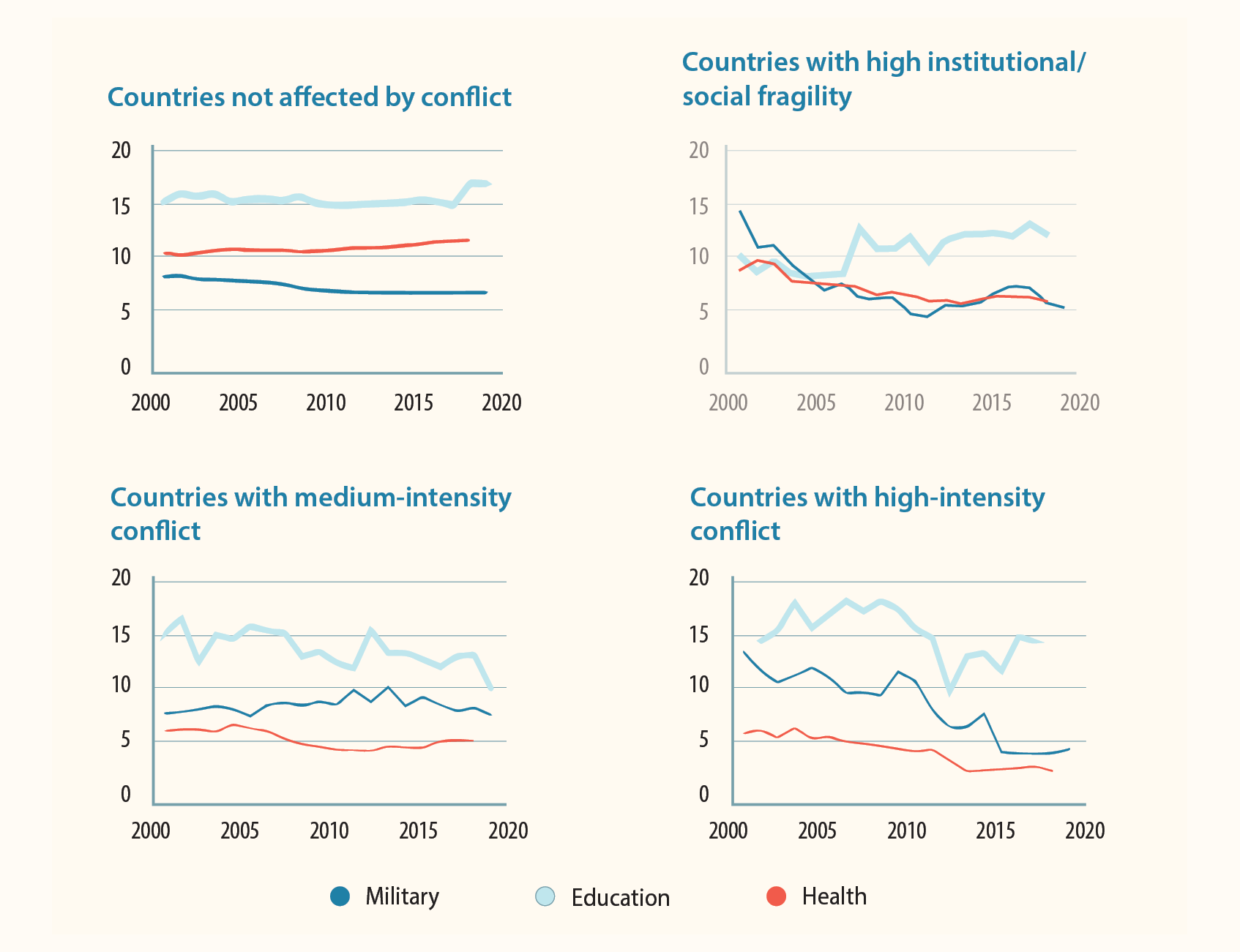

Fragile and conflict-affected countries have tended to spend relatively more on defence than on social protection, whereas countries that are not classified as such depict the opposite trend. In Afghanistan (the only high-intensity conflict country included in this data set), military spending has exceeded one third of total government spending since 2010, whereas less than 4 per cent of government spending has gone towards social protection. In contrast, in countries that are not classified as fragile or conflict-affected, the proportion of State spending going to social protection has been over 25 per cent on average since 2010, with less than 6 per cent of spending going to the military in any given year.

Source (graphs): International Food Policy Research Institute, Statistics on Public Expenditures for Economic Development (SPEED).

Source (caption): Ruth Carlitz, “Comparing Military and Human Security Spending: Key Findings and Methodological Notes” (2021).

Note: The y-axis scale has been adjusted for the graph for countries with high-intensity conflict.

In countries not considered fragile or conflict-affected, Governments have tended to spend nearly twice or three times as much on health and education versus their militaries. While education spending still outpaces expenditure on defence in conflict-affected countries, military spending is typically more than twice the proportion spent on health.

Source (graph data): World Bank World Development Indicators.

Source (caption): Ruth Carlitz, “Comparing military and human security spending: key findings and methodological notes” (UN-Women, 2022).