Seventy-five years since the founding of the United Nations and since the horrific bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world continues to live in the shadow of nuclear catastrophe.

In 2020, the world marked several key milestones related to nuclear weapons, including, notably, the seventy-fifth anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Highlights included the fiftieth anniversary of the entry into force of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty), as well as the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Treaty’s indefinite extension.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic did not slow the growth of nuclear risks in 2020; in some cases, it exacerbated them. Meanwhile, nuclear disarmament efforts continued to face obstacles that included deteriorating geostrategic conditions, growing distrust and acrimony among nuclear-armed States, increasing concerns about technological developments contributing to greater risks and ongoing qualitative improvements to nuclear weapons.

In recent years, States possessing nuclear weapons have stepped up nuclear modernization efforts, resulting in the development of new weapons systems, qualitative improvement of existing systems and the development of new nuclear-capable platforms. It has been argued that the modernization programmes of the five nuclear-weapon States identified in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty are inconsistent with commitments undertaken as parties to the Treaty.

China’s nuclear arsenal modernization efforts include the development of the Type 094 and Type 096 ballistic-missile submarines, the JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile and road-mobile missile systems such as the DF-41 intercontinental ballistic missile, which will replace older, silo-based systems.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is in the process of developing and testing various delivery systems capable of delivering nuclear weapons. Recent ballistic-missile tests have focused on developing both its short-range and submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

France’s nuclear modernization campaign includes modernization of its submarine-launched ballistic missiles and their associated TNO warheads, refurbishment of its ASMP-A air-launched cruise missiles and the development of a third-generation ballistic-missile submarine for use in the 2030s.

India’s nuclear modernization programme focuses on the creation of a strategic nuclear triad and the establishment of a credible nuclear deterrent. India is developing an indigenous ballistic-missile submarine, enhancing its submarine-launched and long-range ballistic missile capabilities, and increasing the size of its nuclear arsenal.

While Israel is generally purported to have nuclear weapons, it officially neither confirms nor denies that it possesses them.

Pakistan is expected to increase its nuclear arsenal and continue actively augmenting its nuclear-capable ballistic and cruise missiles over the next decade. Additionally, Pakistan is developing the Babur-3 SLCM in a bid to develop a nuclear triad and ensure a secure second-strike capability.

The Russian Federation’s strategic and non-strategic nuclear force modernization includes retiring and replacing Soviet-era missile systems, the introduction of Borei- class ballistic-missile submarines and the integration of several new types of nuclear-capable delivery systems.

The United Kingdom aims to replace its current group of four Vanguard-class ballistic-missile submarines with four Dreadnought-class ballistic-missile submarines by the early 2030s. The country has also begun to improve the lifespan of the Trident Holbrook warhead.

The United States’ nuclear modernization plan involves all three legs of its strategic nuclear triad. It includes the development of the Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines, the F-35A nuclear-capable tactical fighter-bomber, and the Grand-Based Strategic Deterrent and Long-Range Standoff systems. The United States also aims to increase plutonium core production and modernize the command-and-control systems of its Department of Defense.

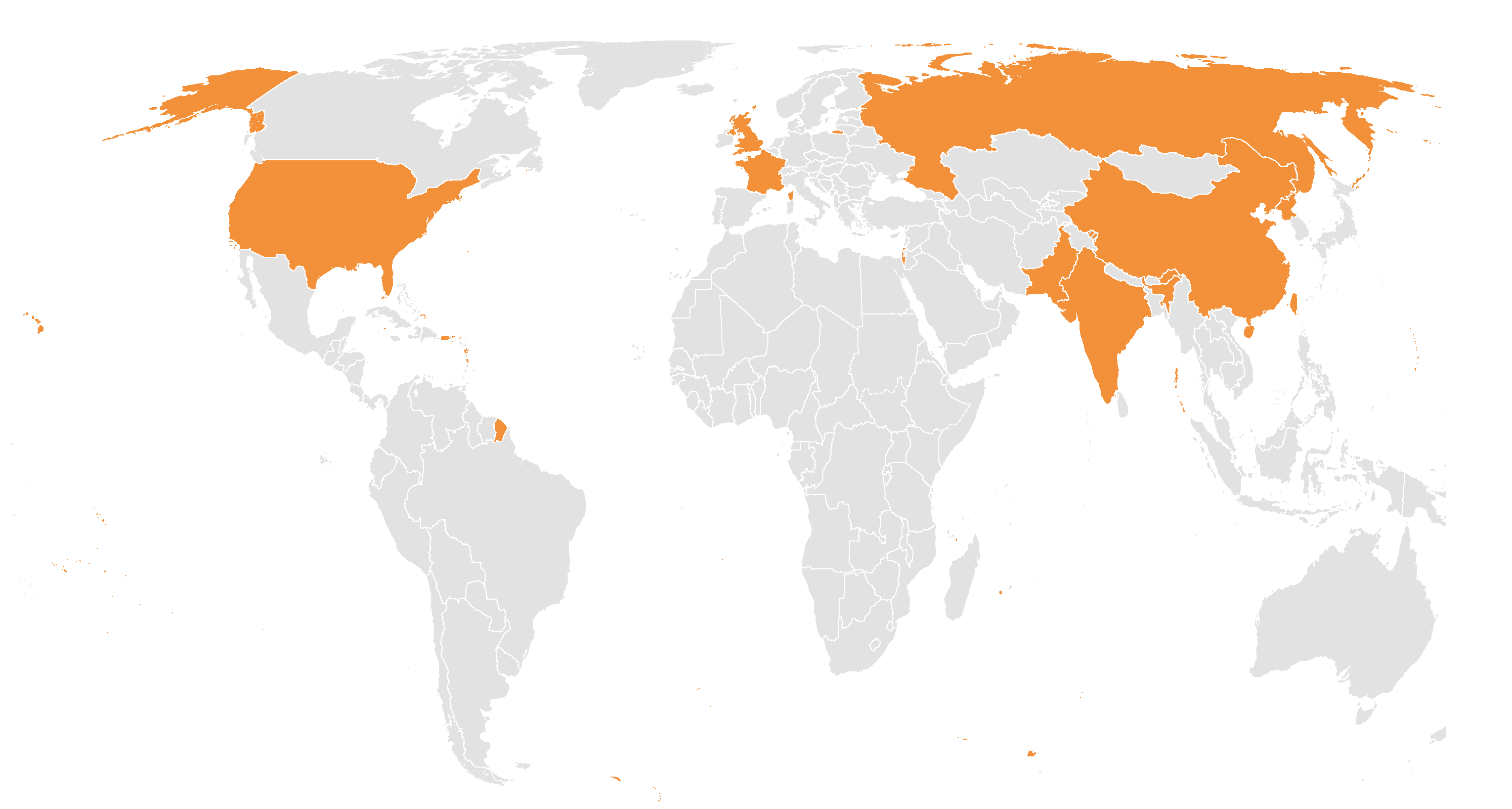

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the Parties. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of the Abyei area is not yet determined.

Map source: United Nations Geospatial Information Section.

Those negative trends served to further erode the global disarmament and non-proliferation regime, both undermining past accomplishments and impeding further progress. In 2020, the harm from those trends was made worse by the postponement of key forums related to nuclear disarmament, as well as the growing divergences between Member States over how to achieve the common goal of eliminating nuclear weapons. The Secretary-General highlighted the stakes in his message to the Nagasaki Peace Memorial Ceremony on 9 August, stating, “The historic progress in nuclear disarmament is in jeopardy, as the web of instruments and agreements designed to reduce the danger of nuclear weapons and bring about their elimination is crumbling. That alarming trend must be reversed.”

Izumi Nakamitsu, High Representative for Disarmament Affairs (second from right, front row), meets young people in Japan on 10 August 2020 at an event to mark the 75th anniversary of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and the establishment of the United Nations.

At the onset of the pandemic, the States parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty decided to postpone the agreement’s tenth Review Conference to help ensure the health and safety of delegates. After initially postponing the Conference until January 2021, those States decided, in light of the ongoing pandemic, to hold the meeting from 2 to 27 August 2021 and to take a final decision on dates in 2021. While the postponement of the Review Conference delayed much-needed, vital dialogue on issues related to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, it also provided the States parties with additional time to narrow divergences and overcome barriers to a consensus outcome at the Conference.

As relations between States possessing nuclear weapons continued to decline in 2020, risks from those weapons grew as they assumed a larger role in national defence strategies. In February, the United States fielded a low-yield, submarine-launched nuclear weapon, envisaged in its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review “to address the conclusion that potential adversaries, like Russia, believe that employment of low-yield nuclear weapons will give them an advantage over the United States and its allies and partners”. In June, the Russian Federation released its updated “Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence”. While the publication of those principles for the first time was a useful transparency measure, the updated principles arguably lowered the threshold for nuclear-weapon use by expanding the number of scenarios in which they could be used.

Meanwhile, the network of arms-control and confidence-building instruments and arrangements was further weakened when, on 22 November, the United States ceased to be a party to the Treaty on Open Skies. Its stated reason for withdrawal was non-compliance by the Russian Federation. The remaining Parties agreed to continue their participation as observers, underscoring the Treaty’s value as both a confidence-building measure and a significant achievement for arms control.

Following the dissolution in 2019 of the Treaty between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty), in October 2020, the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, offered to add “mutual verification measures” to his proposal, first put forward in 2019, for a moratorium on the deployment of missiles previously banned by the Treaty. The United States rejected the proposal because the Russian Federation had already deployed four battalions of intermediate-range missiles within range of European States.

In a more positive development, arms control negotiators from the United States and the Russian Federation engaged in four rounds of dialogue in Vienna during the year. Participants in the talks discussed issues related to strategic stability, including the possible extension of the Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START Treaty) before the Treaty’s expiration in February 2021. China declined an invitation by the United States to participate, however, due to the disparity in the sizes of their respective nuclear arsenals. Although the Russian Federation and the United States were ultimately unable to agree to an extension, the discussions were a welcome step in dialogue between the possessors of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals.

In 2020, all States that possessed nuclear weapons continued to modernize their nuclear arsenals, including by developing, testing and deploying new nuclear-capable weapons systems. The Russian Federation tested new submarine-launched ballistic missiles and a hypersonic cruise missile, deployed missiles armed with a hypersonic glide vehicle and continued to develop weapons systems announced by President Putin in 2018. The United States, in addition to deploying a new low-yield nuclear warhead, tested a hypersonic glide vehicle and continued with plans to replace its land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, air-launched cruise missiles, and nuclear-capable bombers and submarines. Throughout 2020, China conducted tests of both medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles; achieved further progress towards developing a road-mobile nuclear arsenal, including a solid-fuelled intercontinental ballistic missile; and moved closer to establishing a full nuclear triad, with weapons deployable by land, air and sea.

There was no resolution to regional situations with nuclear dimensions in 2020. The Islamic Republic of Iran continued to scale back compliance with its nuclear commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, countering the reimposition of sanctions by the United States in 2018. The Islamic Republic of Iran’s ongoing actions, which included installing new uranium-enrichment centrifuge types and accelerating research and development, resulted in significant growth in its stockpile of low-enriched uranium and a further increase in its enrichment potential. It maintained that all steps were reversible. In response to the Islamic Republic of Iran’s violations of the Plan of Action, in September, the United States claimed to have activated the “snap back” mechanism in the Security Council, triggering the reimposition of all United Nations sanctions on the nuclear programme of the Islamic Republic of Iran. A strong majority of Security Council members rejected the United States’ position.

Tensions also persisted on the Korean Peninsula, which saw no progress during the year in the implementation of the joint statement by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the United States from the Singapore summit in June 2018. While the United States signalled that it remained open to negotiations and extended several diplomatic overtures, the COVID-19 pandemic hindered further diplomatic engagement with a view to the complete and verifiable denuclearization of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Despite those negative trends, several developments were causes for optimism in 2020 in the pursuit of a world free of nuclear weapons. Action items under “Disarmament to Save Humanity”—the pillar of the Secretary- General’s Agenda for Disarmament dedicated to eliminating all nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction—gained three new State “champions” and 11 “supporters” during the year. States also stepped up cross-regional initiatives in support of a successful Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, including the development of 22 proposals to reduce nuclear risks and achieve progress in nuclear disarmament.

Additionally, the conditions for the entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons were met in October, representing what both the Secretary-General and the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs described as a meaningful commitment to nuclear disarmament and multilateralism. As the first multilateral nuclear disarmament treaty to be negotiated in over 20 years, the agreement was a testament to the survivors of nuclear bombings and tests, many of whom had advocated for it.

Despite the postponement of the fourth Conference of Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones and Mongolia, States continued working to strengthen both the implementation of treaties establishing such zones and coordination between zones. In that regard, their work included support for centralized coordination mechanisms, as well as webinars aimed at strengthening implementation in the individual zones. Likewise, despite the postponement of the second negotiating conference on a Middle East zone free of nuclear weapons and all other weapons of mass destruction, a workshop exploring the lessons learned from existing nuclear-weapon-free zones was organized in July to maintain momentum for negotiations.

General and complete disarmament is one of the core goals of the United Nations as enshrined in its Charter, adopted in 1945. In pursuit of this universal objective, Member States, over the span of more than seven decades, have produced a multitude of treaties, agreements, initiatives and norms in the sphere of nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation and arms control that vary in their nature, scope of application and membership. This graphic highlights the key elements of that treaty framework, widely referred to as “the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime”.

More information on the treaties, agreements, initiatives and norms is available below.

Multilateral agreements

NPT. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, is the cornerstone of the global nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime. It is built upon three pillars: nuclear non-proliferation, nuclear disarmament and peaceful use of nuclear energy.

United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution 1540 (2004) requires all States to refrain from providing any form of support to non-State actors that attempt to develop; acquire; manufacture; possess; transport; transfer; or use nuclear, chemical or biological weapons and their means of delivery.

CTBT. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty bans all nuclear explosions by everyone, everywhere: on the Earth’s surface, in the atmosphere, underwater and underground. The Treaty also has a unique and comprehensive verification regime to monitor potential nuclear explosions.

PTBT. The Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, also known as the Partial Test Ban Treaty, prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted underground. The Treaty has been de facto succeeded by the CTBT.

CPPNM. The Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (including its 2005 Amendment) is the only international legally binding undertaking in the area of physical protection of nuclear material. It establishes measures related to the prevention, detection and punishment of offences relating to nuclear material. The amended Convention makes it legally binding that States Parties protect nuclear facilities and material in peaceful domestic use, storage and transport.

ICSANT. The International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism joined the previously existing universal anti-terrorism conventions, strengthening the international legal framework in connection with terrorist acts and further promoting the rule of law. The Convention enables the criminalization of planning, threatening, or carrying out acts of nuclear terrorism.

Sea-bed Treaty. The Treaty on the Prohibition of the Emplacement of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor and in the Subsoil Thereof is a multilateral agreement banning the placing of weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons, on the ocean floor beyond a 12-mile coastal zone.

Antarctic Treaty. The Antarctic Treaty obligates parties to use Antarctica only for peaceful purposes. Military activities are prohibited, including the testing of weapons, nuclear explosions, and the disposal of radioactive waste in Antarctica.

Outer Space Treaty. The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies obligates parties not to place any objects carrying nuclear weapons in orbit, on the Moon or on other celestial bodies.

TPNW. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is the most recently adopted multilateral disarmament agreement and includes a comprehensive set of prohibitions on participating in any nuclear- weapon activities. Those include undertakings not to develop, test, produce, acquire, possess, stockpile, use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.

Plurilateral agreements

Treaty of Tlatelolco. The Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean, the first treaty of its kind to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone (NWFZ) in a densely populated area, prohibits Latin American and Caribbean States from acquiring, possessing, developing, testing or using nuclear weapons, and prohibits other countries from storing and deploying nuclear weapons on their territories.

Rarotonga Treaty. The South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty was born from the South Pacific’s first-hand experience with nuclear weapons testing and was the second NWFZ in a populated region to enter into force. The geographic scope of the Treaty is vast, extending from the west coast of Australia to the boundary of the Latin American NWFZ in the east, and from the equator to 60 degrees south, where it meets the boundary of the zone established by the Antarctic Treaty.

Bangkok Treaty. The Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone is a key legal instrument in preserving South-East Asia as a zone free of nuclear weapons and all other weapons of mass destruction. It also reaffirms the importance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and in contributing towards international peace and security.

Pelindaba Treaty. The African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty established the NWFZ on the African continent. The Treaty prohibits the research, development, manufacture, stockpiling, acquisition, testing, possession, control or stationing of nuclear weapons, as well as the dumping of radioactive wastes.

CANWFZ Treaty. The Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia is a legally binding commitment by Central Asian States not to manufacture, acquire, test, or possess nuclear weapons. The creation of the zone was driven by the common desire of Central Asian States to provide security, stability and peace in the region, address environmental concerns and create the necessary conditions for regional development and stability.

Lisbon Protocol. The Protocol to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty of 1991 (START I) was signed by representatives of the Russian Federation (originally the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR)), Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan recognizing the four States as successors of the USSR and its obligations under START I. The Protocol also established the necessary political framework for Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine to accede to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as non-nuclear-weapon states.

The Treaty on Open Skies promotes openness and transparency of military forces and activities through a programme of unarmed aerial surveillance flights over the entire territory of its participants, spanning from North America to most of Europe and the Russian Federation. The Treaty is designed to enhance mutual understanding and confidence by giving all participants the opportunity to gather information about military forces and activities of concern to them.

JCPOA. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action is an agreement on the Islamic Republic of Iran’s nuclear programme that was reached in Vienna on 14 July 2015, between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany and the European Union. The nuclear deal was endorsed by the United Nations Security Council (resolution 2231 (2015)). The Islamic Republic of Iran’s compliance with the agreement’s nuclear-related provisions is verified by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Bilateral agreements

Hot Line Agreement. The Washington-Moscow Direct Communications Link, which emerged shortly after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, is a system that allows direct communication between the leaders of the United States (US) and the USSR/Russian Federation. The need for ensuring quick and reliable communication directly between the Heads of Government of nuclear-weapon States emerged in the context of efforts to reduce the risks of nuclear confrontation due to accident or miscalculation.

SALT I. The Interim Agreement between the US and the USSR on Certain Measures with Respect to the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms was an executive agreement that capped US and Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missile forces.

SALT II. The Treaty Between the US and the USSR on the Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms, together with agreed statements and common understandings regarding the Treaty, was the first nuclear arms treaty between the US and the USSR that assumed real reductions in strategic forces to a combined 2,250 of all categories of delivery vehicles on both sides.

TTBT. The Treaty between the USSR and the US on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests, also known as the Threshold Test Ban Treaty, was signed in July 1974 by both States. It established a nuclear “threshold“ by prohibiting nuclear tests of devices having a yield exceeding 150 kilotons after 31 March 1976.

PNET. In preparing the TTBT in July 1974, the US and the USSR recognized the need to establish an appropriate agreement to govern underground nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes. The Treaty on Underground Nuclear Explosions for Peaceful Purposes (negotiated in April 1976), which is also known as the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty, governs all nuclear explosions carried out at locations outside the weapons test sites specified under the TTBT while also limiting maximum allowed yields of such explosions.

Reagan-Gorbachev declaration. In a statement after their summit in Geneva, in November 1985, US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev declared that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”, which came to be known as the Reagan-Gorbachev Principle.

INF Treaty. The Treaty Between the US and the USSR on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles banned all the two nations’ land-based ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and missile launchers with ranges of 500–1,000 kilometres (short medium-range) and 1,000–5,500 km (intermediate-range). The agreement did not apply to air- or sea-launched missiles. The Treaty was terminated in 2019.

Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. The Treaty Between the US and the USSR on the Limitation of Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems was an arms control treaty on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile systems used in defending areas against ballistic missile-delivered nuclear weapons. Per the Treaty, each party was limited to two anti-ballistic-missile complexes, each of which was to be limited to 100 anti-ballistic missiles. The Treaty was terminated in 2002.

START I. The Treaty Between the US and the USSR on Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms barred its signatories from deploying more than 6,000 nuclear warheads atop a total of 1,600 ICBMs and bombers. START was the largest and most complex arms control treaty ever negotiated, and its final implementation in late 2001 resulted in the removal of about 80 per cent of all strategic nuclear weapons then in existence.

START II. The Treaty Between the US and the Russian Federation on Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms was intended to ban the use of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles on ICBMs. Despite continued negotiations, it never entered into force.

SORT. The Treaty between the Russian Federation and the US on Strategic Offensive Reductions (SORT) was a strategic arms reduction treaty between the US and Russian Federation limiting their nuclear arsenal to between 1,700 and 2,200 operationally deployed warheads each. It was eventually superseded by the New START Treaty.

New START Treaty. The Treaty between the US and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms limits the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons to 1,550 per State and 800 total launchers. Originally scheduled to expire on 5 February 2021, the New START Treaty was extended for an additional five years.

Unilateral initiatives

The global nuclear testing moratorium is an informal behavioural norm adhered to nearly universally since 1998, after the formal cessation of nuclear tests by the US and USSR. It was further reinforced by the adoption of the CTBT in 1996.

The US-Soviet presidential nuclear initiatives is a framework of reciprocal initiatives by the presidents of the US and the USSR/Russian Federation (declared in 1991 and 1992) that sought to limit and reduce the tactical nuclear- weapon arsenals of the two States by removing excessive and unnecessary nuclear payloads from ships, submarines, land-based naval aircraft, artillery munitions and mines.

The nuclear arsenal reductions of France and the United Kingdom are significant unilateral initiatives of those countries in the mid-1990s along with a parallel adoption of “minimum deterrence” policies.

Mongolia’s nuclear-weapon-free status. Mongolia, as a State committed to non-proliferation of nuclear weapons in all its aspects and to achieving nuclear disarmament, declared its territory an NWFZ in September 1992. This unique status was recognized by the United Nations General Assembly through its resolution 53/77 D, first adopted in 1998 without a vote.