If threats to international peace and security are to be adequately addressed, small arms and light weapons must be considered regularly and across issue areas.

The challenges posed by conventional arms grew throughout 2020. Across much of the globe, illicit flows and misuse of small arms and light weapons and their ammunition contributed directly to pervasive armed violence in rural and urban settings, including through transnational organized crime and terrorism. While major armed conflicts persisted across the world—including in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Mali, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen—new instances of sustained armed violence emerged in Cameroon, Ethiopia and Nagorno-Karabakh, further heightening the urgency of dialogue and activities to address illicit arms flows.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated both the above-mentioned challenges and the difficulty of implementing global and local arms control measures, thus contributing to negative impacts on peacebuilding and post-conflict development. Illicit arms networks leveraged higher unemployment and civil unrest to their advantage with diminished resistance from weakened institutions and overburdened public services. In that context, multiple actors continuously underlined the urgency of reining in conflict in the face of the global public health emergency; in March the Secretary-General called for an immediate global ceasefire, and the Security Council supported his appeal with its adoption of resolution 2532 (2020) in July. Regrettably, the global focus on addressing the pandemic still did not produce a cessation of armed conflict, and global military spending continued to rise.

In the face of those setbacks, international organizations applied the means at their disposal to tackle those and other challenges from conventional arms. In April, the Secretary-General convened his Executive Committee—made up of heads of United Nations departments, offices and agencies—to reflect on the role of conventional-arms control in his vision for “disarmament that saves lives”.

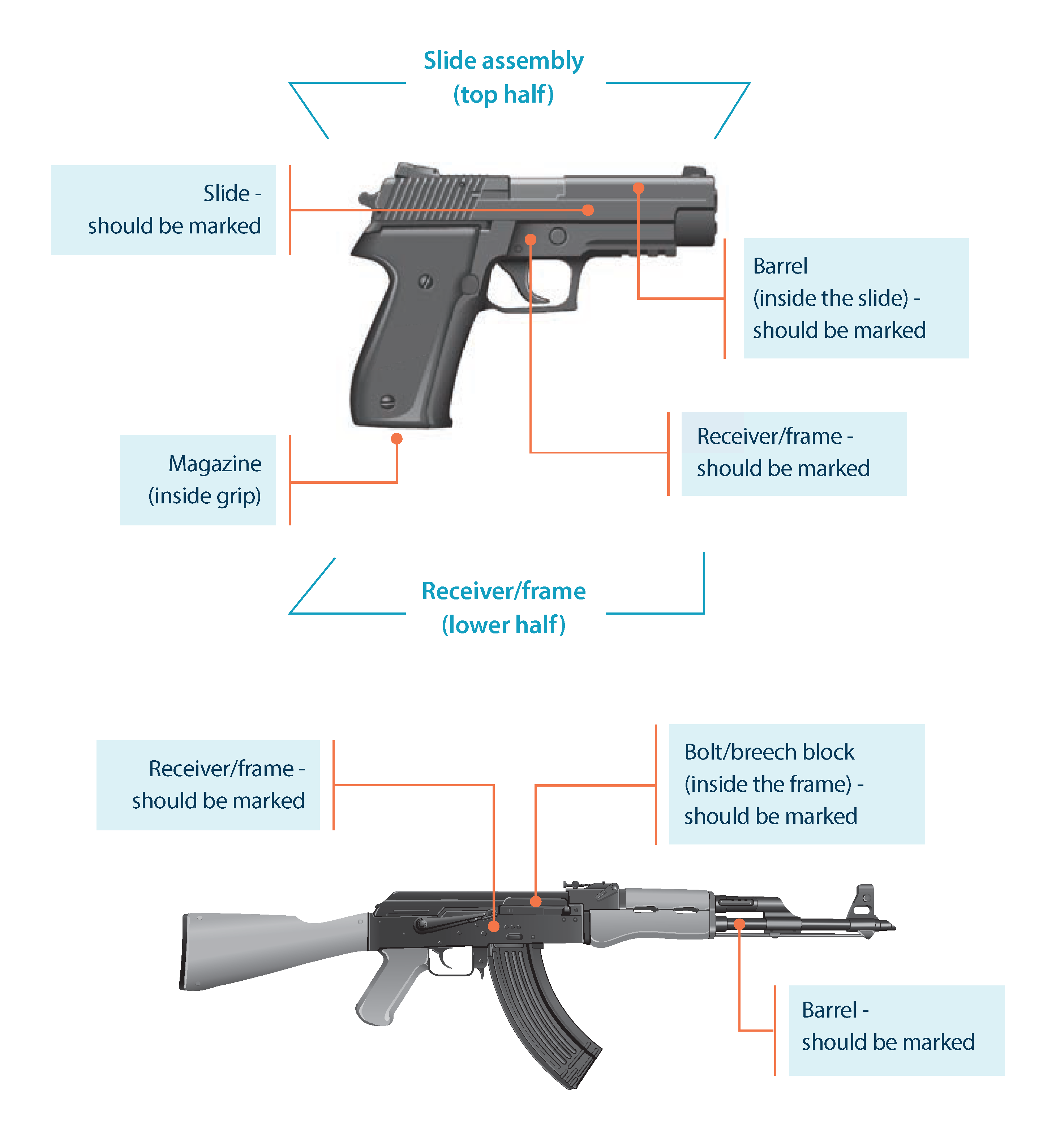

Marking weapons is a critical measure in the fight against illicit trafficking. Once a weapon is emblazoned with a unique identifier, authorities can identify the point of “diversion” if it is moved from the legal to illegal realm. A marked weapon can also be “traced”, or systematically tracked through the lines of supply to where it was manufactured or most recently imported. That process provides information that can support enforcement of arms embargoes or identification of trafficking routes, among other activities.

In accordance with the International Tracing Instrument, a marking should be applied to an essential or structural component of the weapon, such as its receiver or frame. States are also encouraged to mark other parts of the weapon, like its barrel and slide or cylinder. More information on marking and tracing can be found in MOSAIC, a set of voluntary, practical guidance notes combining the best small-arms expertise in succinct, operational advice.

Illustrations courtesy of Small Arms Survey.

In 2020, instances of progress were still seen in efforts to address the safety and security of conventional ammunition stockpiles, despite the pandemic necessitating the postponement to 2021 of the seventh Biennial Meeting of States to review the implementation of the Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons. Drawing on informal consultations convened by Germany throughout 2018 and 2019, a group of governmental experts held an in-person meeting in January, followed by virtual, informal discussions in April. In those discussions, the experts initiated a process of comprehensive consideration to both safety and security aspects of conventional ammunition management.

As the use of explosive weapons in populated areas remained a major security and safety concern for civilians around the world, a group of States continued developing a political declaration on the humanitarian impact of such use. Building on an initial consultation held in 2019, Ireland continued to steer work on a draft declaration by organizing a second consultation in February and subsequently welcoming virtual inputs.

Progress was also seen in the implementation of relevant funding mechanisms. Working with the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs began preparing to launch the first pilot projects of the Saving Lives Entity, a funding facility established in 2019 within the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund. Cameroon and Jamaica were expected to be early beneficiaries of the new trust facility, designed to help Member States tackle illicit small arms and light weapons as part of a comprehensive and programmatic approach to sustainable security and development. Meanwhile, in a separate development, the United Nations Trust Facility Supporting Cooperation on Arms Regulation continued to support 14 projects for its 2019– 2020 cycle, as well as 16 projects initiated in 2018.

Youth leaders displaying their Africa Amnesty Month shirts at a local sensitization workshop held in Hola, Tana River County, Kenya, in September 2020.

In the second half of the year, the Office for Disarmament Affairs joined the African Union Commission and the Regional Centre on Small Arms in the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa and Bordering States to assist seven African States in processing the weapons surrendered to authorities as part of Africa Amnesty Month. As part of the broader support from the United Nations for the African Union’s flagship initiative, referred to as “Silencing the Guns”, the Office and its project partners collaborated with the national commissions and focal points on small-arms control in beneficiary countries to identify needs and develop country-specific programming. To support nationwide outreach campaigns in those States, the Office also assisted in the delivery of gender- and youth-sensitive messaging that highlighted the key objectives of the Silencing the Guns initiative. Such messages were also intended to raise awareness about the devastating impacts of the illicit proliferation of small arms on sustainable peace and development.

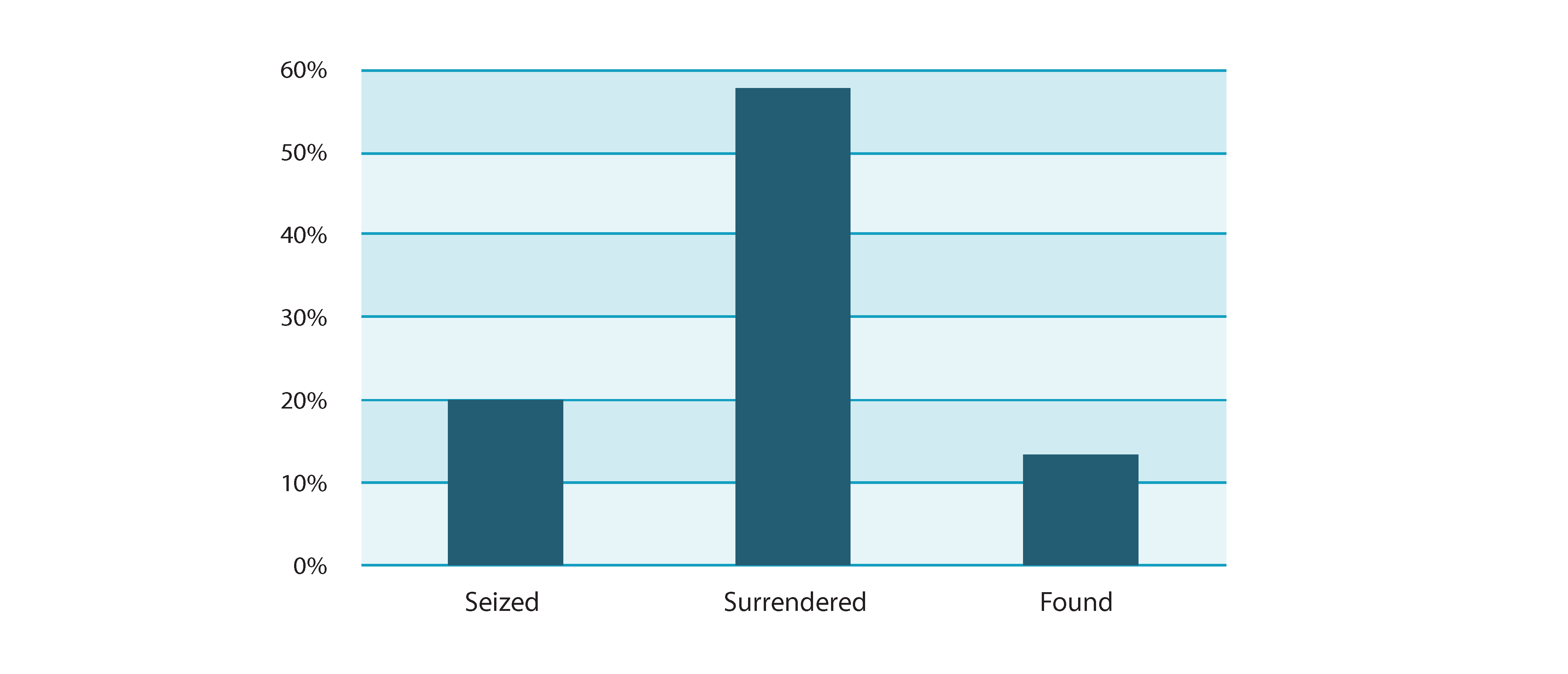

According to data collected by 13 African States under the United Nations Programme of Action on Small Arms and Light Weapons, voluntary surrender was the primary means of weapons collection in 2018 and 2019. The African Union and the United Nations aimed to enhance that trend in 2020 and 2021 by supporting national institutions responsible for small-arms control and assisting operational entities in areas like sensitization, outreach and capacity-building. Those activities—undertaken to mark Africa Amnesty Month for the surrender and collection of illicit small arms and light weapons—support participating States in weapons collection and other areas likely to be reflected in their 2022 reports for the Programme of Action.

In 2020, fewer Member States reported to the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms and the United Nations Report on Military Expenditures than in the previous year. While the ongoing pandemic may have contributed to the drop in participation, the decline in reporting was a continuation of a decade-long downward trend. There was also a slight decrease in the number of States declaring their transfers of small arms and light weapons as part of their reporting for the Register, from 27 in 2019 to 26 in 2020. Meanwhile, the Office for Disarmament Affairs continued to oversee an upgrade of the database used by Member States to submit their military expenditures; the project was scheduled to conclude in the first quarter of 2021.

The Office for Disarmament Affairs also further developed the Modular Small-arms-control Implementation Compendium (MOSAIC, publicly releasing three new modules in 2020. Additionally, to facilitate the use of MOSAIC by a larger number of countries and entities, the Office continued to oversee the translation of previously approved modules into languages other than English.

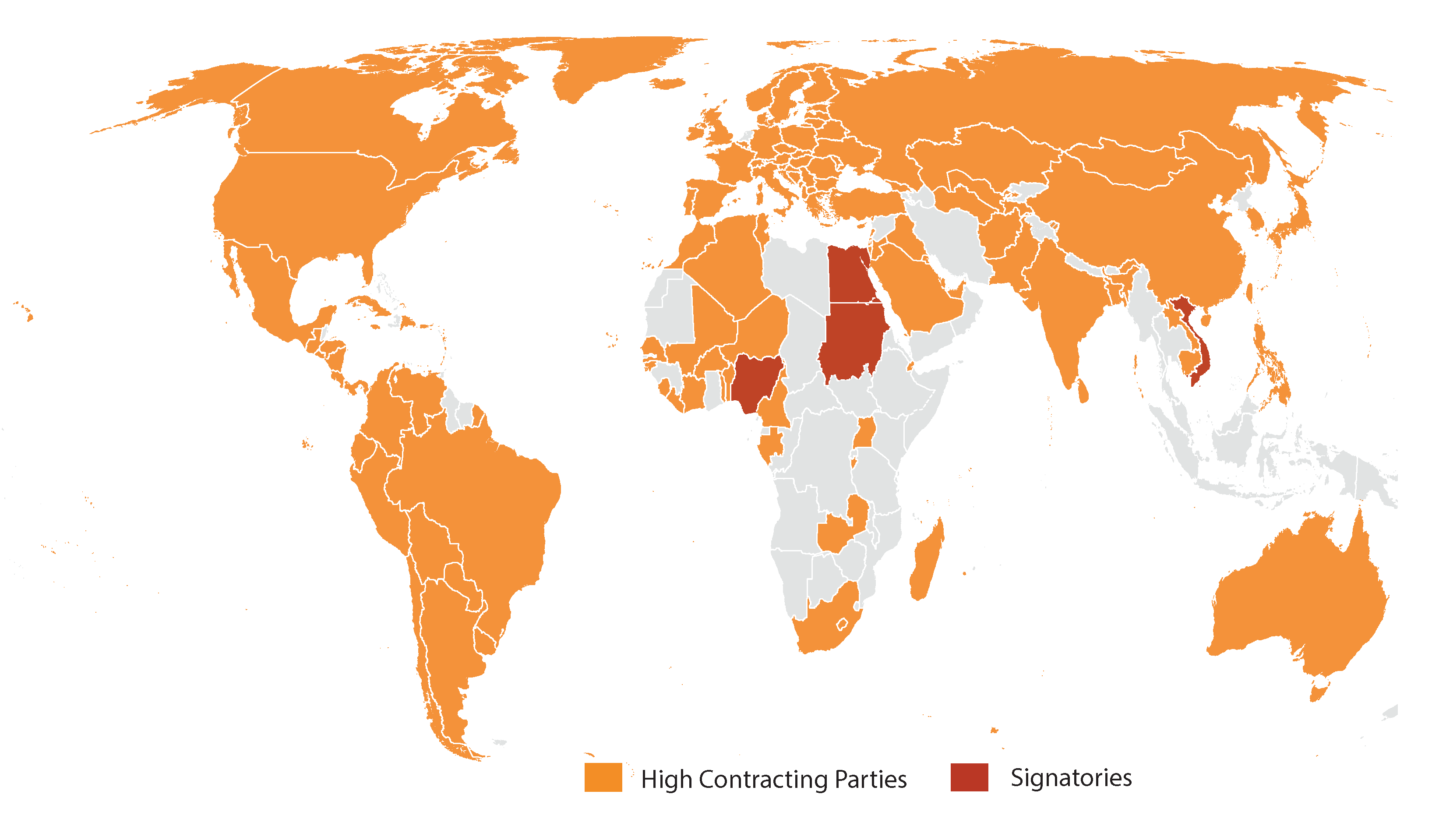

The map above shows the High Contracting Parties and signatories to the framework agreement of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. For information on adherence to the Convention's Protocols and Amendments, refer to the Disarmament Treaty Database.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the Parties. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of the Abyei area is not yet determined.

Map source: United Nations Geospatial Information Section.

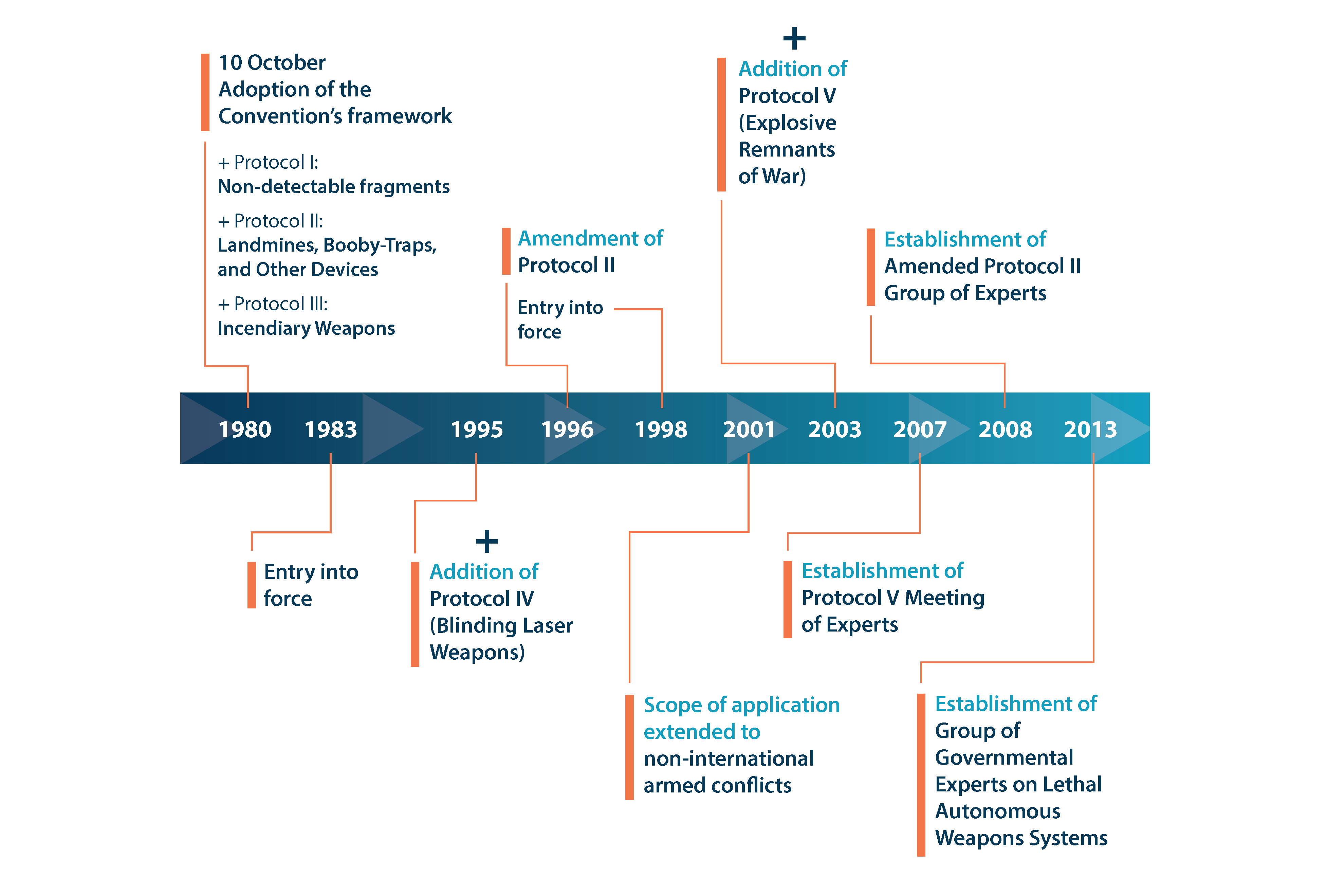

The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, adopted in 1980, entered into force in 1983 with the aim of banning or restricting the use of specific types of weapons considered to cause unnecessary or superfluous suffering to combatants or to affect civilians indiscriminately.

The flexible design of the Convention, which contained only a framework treaty and three protocols (Protocols I–III) at its inception, subsequently allowed the agreement to evolve in response to emerging challenges, weapons developments and a changing international climate.

The addition of Protocol IV, on blinding laser weapons, in 1995 marked the first pre-emptive ban on a weapon yet to be used on the battlefield.

Then, in 2003, States parties added Protocol V, on explosive remnants of war, the first multilateral agreement to deal with the problem of unexploded and abandoned ordnance after the cessation of hostilities.

Other changes included a 1996 amendment to Protocol II in response to the humanitarian consequences of landmines, as well as a decision in 2001 to broaden the scope of the Convention and its protocols to apply to non-international armed conflicts.

In the following years, the international community continued to actively discuss issues ranging from improvised explosive devices and incendiary weapons to lethal autonomous weapons systems, seeking to progressively develop norms and rules that ban or restrict weapons that could not be used in conformity with the principles of international humanitarian law.